Nothing is perhaps sadder than a life whose promise remains unfulfilled. Such was the case with countless young men who died in the AIDS pandemic in the 80s and 90s before a practical therapy was developed. One such individual was the 33-year-old mixed media artist Darrel Ellis, whose innovative work is currently on display in a special exhibition at the Columbia Museum of Art.

Among the countless individuals who fell victim to an AIDS-related illness in those early years were notable American photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar, both friends of Ellis. Photography became a principal creative medium for Ellis as well, but he was not content to let the camera do all the work.

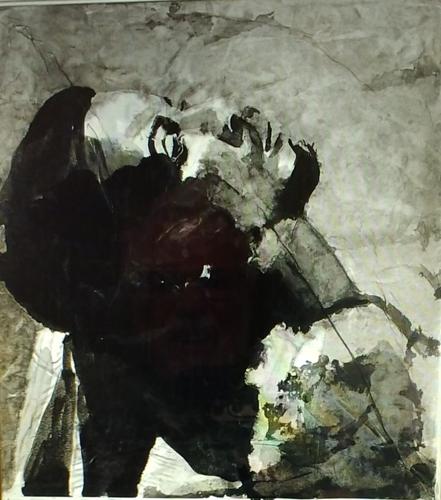

Ellis most often used a photograph as a reference point for drawings and paintings. A good example of this approach is the signature piece of the current show, a self-portrait of the artist inspired by a Peter Hujar photograph. On display at the CMA are both the original Hujar silver gelatin print produced in 1981 and the black ink, wash and charcoal rendering made by Ellis eight years later. In both images, Ellis is seen in profile, his shoulder bared. The paper drawing the artist subsequently mounted on canvas, thus amplifying the seductive quality of the pose with additional surface interest.

The piece in the current show that best showcases Ellis’s experimentation with surface treatment is, however, a manipulated portrait of Joseph Tansle, his great uncle.

A piece by Darrell Ellis, whose work is featured in the Columbia Museum of Art until Summer 2024.

Based on a distorted photographic image of his male relative — the lower half of the face appears to bow outward — Ellis created between 1989 and 1991 a graphite and ink likeness on a wood panel whose surface is encrusted with modeling paste. The resulting work reads like a low-relief sculpture. The surface irregularities combined with the fishbowl effect of the camera image provide an effective incarnation of how memory works. Nothing is ever sharply focused.

Critics seem to agree that Ellis was obsessed with capturing the passage of time, most often either moments in the social life of his extended family or, especially after his HIV diagnosis, phases of his own physical and psychological decline.

In chronicling the life of his family, so many of the photographs that he chose as his source material were from a collection he had inherited from his late father, a man he never knew — Thomas Ellis, a postal worker and amateur photographer, was killed during a police altercation in the 1950s.

The current show includes, for example, a triple portrait that Thomas Ellis took circa 1953 of himself, his wife and his daughter. His father’s vintage photograph is juxtaposed with the artist’s acrylic and charcoal reworking of the same trio; but in this case, the central figure of his father is almost completely wiped out with thick white horizontal brushstrokes, as if he had been erased from history. The artist’s sensitive exploitation of his father’s photos is thus a way of commemorating his parent’s tragically truncated place in the family narrative.

The same might be claimed for the variety of self-portraits in the present exhibition.

Even before his HIV diagnosis around 1984, Ellis was using himself as a subject for his figurative drawings and paintings, most based on either selfies or photographs taken by others. The number of self-portraits increased dramatically after his participation in a 1989 group show in New York entitled “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing.”

That now-iconic exhibition, which featured works by Hujar, Mapplethorpe, Mark Morrisroe, David Wojnarowicz and Ellis along with a score of other artists lost to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, gained front-page headlines because it called attention to all the creative people whose untimely deaths were due to AIDS-related causes.

A piece by Darrell Ellis, whose work is featured in the Columbia Museum of Art until Summer 2024.

One particular self-portrait from that final phase — yet another graphite and ink drawing over acrylic modeling paste on paper — shows the artist, his knit-capped head tilted to the side and his open palms outstretched toward the viewer in a gesture of supplication. Did the artist deliberately choose to depict himself as one of society’s outcasts, pleading for some acknowledgment of his plight?

Co-organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Bronx Museum of the Arts, “Darrel Ellis: Regeneration” runs until May 12 at the Columbia Museum of Art. The show offers not only a showcase for the work of an important African American artist but also a glimpse of the creative spirit of a lost generation.