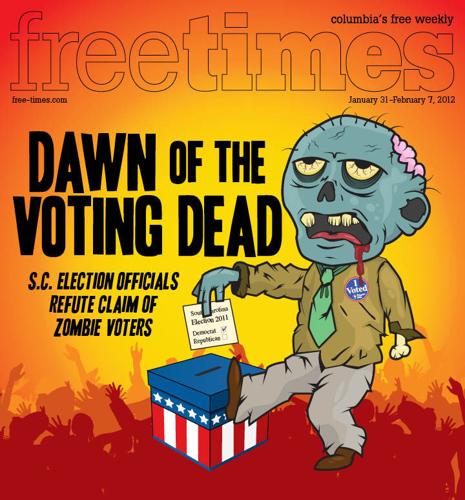

Barbara Zia, president of the League of Women Voters of South Carolina, has a point: Zombie voters make for wonderful headlines, regardless of whether they actually exist. Add the words "South Carolina" into the copy, and you've got a story ready-made for the national news and late-show laugh tracks.

That’s exactly where the zombie voter story has been lately: all over the national media, including Fox News, Huffington Post and the Comedy Central blog, among others.

Of course, dead people can’t vote. They’re dead.

Nonetheless, high-ranking government officials in South Carolina have spent the past few weeks laying out the claim that there have been instances of dead people casting ballots. What frightens people when they hear about dead voters isn’t the specter of a tattered-clothed zombie haunting a polling booth — it’s that if the government is saying dead people voted, it means a very much alive person somewhere has likely committed in-person voter fraud.

But is there voter fraud in South Carolina?

Not according to state election officials, who have beaten back charges in recent weeks that voters have cast ballots from beyond the grave. Last week, State Election Commission director Marci Andino testified that an initial investigation into six names from a list of more than 900 allegedly dead voters has found each one was alive and eligible to vote at the time he or she did so. The agency says it will continue to investigate the entire list.

Meanwhile, the claim of zombie voters making their presence felt at the polls coincides with a face-off between South Carolina and the federal government over the state’s Voter ID law, passed last year. The U.S. Justice Department has blocked implementation of the law, saying it amounts to a form of voter discrimination, a point underscored by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder during a recent visit to Columbia. State officials counter that it’s needed to prevent voter fraud — from zombies or otherwise — and that similar measures passed in some other states have not met with federal resistance.

While the specter of dead voters might seem like a laughing matter, there’s a strong political undertone to the allegations. To put it simply, if dead people were casting ballots, it would strengthen South Carolina’s contention that a Voter ID law is needed.

Zombie Voters, Fraud or Clerical Errors?

It was in December when Republican State Attorney General Alan Wilson said on Fox News that thousands of dead people in South Carolina were on the voter rolls — and implied it was the federal government’s fault if they stayed there.

Then, on Jan. 11, the director of the S.C. Department of Motor Vehicles, Kevin Shwedo, upped the ante with the specific allegation that votes had been cast under the names of deceased individuals.

“Well over 900 individuals appear to have voted after they died,” Shwedo said during a House hearing on the matter. So alarmed was Shwedo that he sent his DMV report to the State Law Enforcement Division for an investigation.

Shwedo based his testimony on DMV analysis that cross-referenced the names of voters in recent elections against mortality data from the Bureau of Vital Statistics and the Social Security Administration’s list of death certificates.

After the report was released, Attorney General Wilson again took to Fox News, saying, “We know for a fact that there are deceased people whose identities are being used in elections in South Carolina.”

Wilson followed up on the matter with a Jan. 19 letter to U.S. attorney Bill Nettles alleging that, according to the DMV data, “953 ballots were cast by voters who were deceased at the time of the election.” In the letter, Wilson told Nettles that he had asked SLED to investigate the matter.

To hear Wilson and Shwedo tell it, you’d think that on Election Day, graveyards all across the Palmetto State had been emptying out and hordes of zombie voters had lurched to the polls. Either that or people in the state had gone to the polls to vote under a false name.

But the State Election Commission maintains that poll managers or county election officials have not heard of any instances in which someone has tried to impersonate another at the polls in South Carolina.

Nationally, in 2008, New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice extensively researched Republican charges of voter fraud and found that it is “more likely that an individual will be struck by lightning than that he will impersonate another voter at the polls.”

So what about those dead folks that supposedly cast ballots in recent elections here? Something else might be going on — something Shwedo even hinted at during his Jan. 11 testimony. While his staff had determined that approximately 950 people might have voted after dying, the DMV director added a caveat: Data-reporting problems or other errors might be to blame.

The Truth is Out There

On Jan. 25, State Election Commission director Andino testified during a subsequent House hearing on the matter. She said her agency had been able to confirm reporting problems in the DMV’s report on dead voters.

Before Andino spoke, Myrtle Beach GOP Rep. Alan Clemmons, who led the hearing, set the tone.

“We must have certainty in South Carolina that zombies aren’t voting,” he said.

The State Election Commission responded in kind.

Andino explained that of the initial batch of six names of allegedly dead voters on the DMV’s list, one had cast an absentee ballot before dying; another was the result of a poll worker mistakenly marking the voter as his deceased father; two were clerical errors resulting from stray marks on voter registration lists detected by a scanner; and two others resulted from poll managers incorrectly marking the name of the voter in question instead of the voter above or below on the list.

Andino, who has 25 years of voter registration and elections experience, didn’t appear all that surprised.

“I can tell you through my experience that while this is unfortunate, it is not uncommon to find cases like this,” she said.

The attorney general’s office had only given the State Election Commission six names off its list of 950 or so names to examine. The agency found every one of them to be alive and otherwise eligible to vote, except for the one who had voted before dying.

During her testimony, Andino directly confronted the DMV’s claim that dead people had voted.

“Characterizing this [alleged fraudulent voting] as an established fact threatens our confidence” in the election process, she said. “This is not a question that needs to linger in the minds of voters ... the truth is out there.”

Andino also appeared slightly disturbed that her agency had first heard about the allegation of dead people voting when Shwedo testified about it on Jan. 11. The agency takes allegations of voter fraud very seriously, she said, and the news of alleged voter fraud also did not sit well with many of the state’s 46 county election commissions.

Some county officials, Andino said, go so far as to check with local funeral homes and pore over obituaries to make sure the names of dead people aren’t showing up on the voter rolls.

The news about zombie voters had been especially concerning to one Pickens County poll worker. The poll worker’s own mother — who appeared to be among the living — was alleged by the DMV to be a deceased voter. It was less a case of her mother being a zombie as it was cause for paraphrasing Mark Twain: The news of her mother’s death had been greatly exaggerated.

“In many cases,” Andino testified, “these are people that our [county election commission workers] know, and these people are very much alive.”

Andino also said that at the time, her agency had not been provided the full list of 950 allegedly dead voters. She said she had been communicating with an investigator in the attorney general’s office to try and get her hands on it. She got the information later that day after the hearing.

That the list had remained something of a state secret for so long disturbed S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus director Phil Bailey, who said that only Republicans at the time had been able to view it.

The reason the attorney general’s office hadn’t made public the list of 950 allegedly dead voters was because it had been handed over to the State Law Enforcement Division for an inquiry into potential criminal activity, according to spokesman Mark Plowden.

Shwedo says that once he passed on the data to law enforcement, he no longer had authority to release it to anyone else. But after being asked by members of the Legislature to give the data to Andino, he did.

The entire spectacle has led to epic eye rolls from voting rights groups such as the League of Women Voters of South Carolina. League president Barbara Zia attended the hearings and has been following the drama closely. She’s afraid so far it’s done more harm than good when it comes to public perception and voter-fraud paranoia.

“It makes a wonderful headline: You can just imagine a zombie army of voters standing ready to march into South Carolina from the state line,” Zia says. “It’s a very powerful image in the media. We feel that it’s kind of a manufactured image.”

Cooking Up a Scandal

Regardless of the DMV’s data apparently not being scrubbed for errors before director Shwedo dropped his dead-voter bomb on Jan. 11, as soon as the report hit the news it was off to the races.

News that an agency director in South Carolina had said in a public hearing — and with an official report in hand — that records showed hundreds of ballots might have been cast from beyond the grave fit nicely into a narrative about the federal government blocking a state bill that would have required voters to flash a photo ID at the polls.

Republicans in the General Assembly had pushed a Voter ID bill for three years and had gotten it passed during last year’s legislative session. After Gov. Nikki Haley signed it, however, the U.S. Justice Department blocked the bill from taking effect on grounds that it was discriminatory and in violation of the federal Voting Rights Act.

Haley and Attorney General Wilson are fighting the federal government’s decision in U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. (Taxpayers could spend as much as $1 million to pay for a high-priced Washington, D.C., lawyer the state has retained at a rate of $520-per hour to take the case, according to the Charleston Post & Courier.)

But before the DMV report had been made public, Wilson was already beating the drum about dead people voting in a state where the feds had blocked a Voter ID law. And he was the one who asked Shwedo to see if any of the 37,000 names of dead people on the voter rolls had been listed as casting a ballot.

On Dec. 28, Wilson told Fox’s Megyn Kelly, “What I do know is, is that the Justice Department’s decision to strike down this law under the Voting Rights Act has preserved the voting rights of 37,000 dead people.”

Roughly two weeks later the public would learn at Shwedo’s hearing that of those 37,000, apparently 950 of them had voted in recent elections, according to the DMV.

Two weeks after that, they would hear that the State Election Commission was refuting such claims, and that the initial six the agency was able to investigate had all come back kosher.

But by then the genie was out of the bottle — the image of the zombie voter was already marching across the public imagination, arms outstretched, groping for a ballot box.

Was it justified, or does DMV director Shwedo think he might have jumped the gun on the dead voter claims?

“The answer is absolutely, unequivocally no,” Shwedo said in a Free Times interview Jan. 30. “If any individual voted any day after the day that they died you have probable cause to believe that a crime had been committed. At the time that it hits the probable cause phase, I am not an investigator, I walk away from it, I pass it on to the attorney general and they in turn passed it on to SLED.”

Shwedo also says he wasn’t planning on beating the dead voter drum himself. But when confronted about it in the Jan. 11 hearing, he merely answered a question the attorney general had asked him to find out a few days prior.

“One of the members of the judiciary [subcommittee] asked the sixty-four thousand dollar question: ‘Were there any of those individuals that were on the 37,000 list that had voted after their date of death?’” Shwedo says. “And the answer was ‘Yes,’ and that’s when the firestorm began.”

That firestorm troubles Matt Gertz, deputy director of research at Media Matters for America.

Upon hearing that there has been no evidence of in-person voter fraud related to the dead voter story so far, his voice was dripping with sarcasm.

“I cannot tell you how shocked I am to hear that,” he said. Media Matters is a progressive, Internet-based nonprofit that monitors, analyzes and corrects “conservative misinformation” in the United States, according to its website.

Gertz had been following the media narrative of South Carolina’s dead voter drives on Fox News for weeks. He says breathless and overblown coverage about suspected voter fraud is part of the network’s bread and butter.

“It’s sort of one of the classic fairy tales of the conservative movement: that there’s this pattern of widespread in-person voter fraud that is happening across the country and putting elections in jeopardy,” Gertz said. “The fact of the matter is that in-person voter fraud is incredibly rare.”

Gertz pointed out that the network has a special voter fraud investigation unit and a voter fraud hotline. He says there’s a reason Fox News appears so interested in a topic in which documented instances of actual in-person voter fraud are so rare.

“Conservatives would like a rationale for passing more restrictive standards to be able to vote — things like Voter ID requirements,” Gertz said. “So it’s in their interest to sort of create this fear that in-person voter fraud is constantly happening, and the only way to stop it is with new laws.”

Finding the Truth

To get to the bottom of the dead-voter drama, SLED has launched an investigation.

“No one in this state should issue any kind of clean bill of health in this matter until the professionals at SLED have finished with their work,” says the state attorney general’s office spokesman Mark Plowden.

Shwedo is pushing a similar message.

“There are a lot of people on both sides of the aisle at the State House trying to make analogies of what to learn from this,” he told Free Times. “The answer is, the investigation is still out. Everybody ought to take a bloody chill pill and wait for the investigation to come through so that people can make intelligent decisions.”

Meanwhile, the State Election Commission will also continue scrubbing all 950 names on the DMV’s dead-voter list for clerical or administrative errors. If they find one voter who has cast a ballot when they shouldn’t have, it would be one too many, Andino says.

Already understaffed and underfunded, the election commission will be stressed as it does so. The agency last week was working to verify the results of a major statewide presidential primary and is also gearing up for the election of every House and Senate member in the state this year.

“It will be a lot of work and the State Election Commission has about 14 or 15 people on staff,” says agency spokesman Whitmire. “If we’re going to get it done quickly we’re going to need more resources.”

In an interview following the Jan. 25 hearing in which Andino had testified that no dead people so far had been confirmed as voting, Rep. Clemmons said the number-one issue on the plate of the Election Commission is “the eroding confidence in our overall election system in South Carolina.”

The Myrtle Beach representative has a history when it comes to claims of voter fraud. He championed the Voter ID bill, and he is also the sponsor of pending legislation that would require third-party organizations that do voter registration drives to register with the state.

Also, while the State Election Commission has repeatedly stated that there have been no documented cases of in-person voter fraud here, Clemmons isn’t sold.

During the state’s battle over Voter ID legislation last year, Clemmons sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Justice in support of the measure that read in part, “It is an unspoken truth in South Carolina that election fraud exists.”

Asked to clarify what he meant in his letter after the hearing Jan. 25, Clemmons declined to go into detail with Free Times.

“If you’ve never heard that in South Carolina, then you need to start talking to folks out there in South Carolina that are involved,” he said.

Asked what kind of fraud he was talking about, Clemmons said, “I’m not making allegations of fraud today, what I’m saying is, we have an election system in South Carolina we’ve got to have total confidence in.”

As for how the public views the election process, the image of a zombie voter doesn’t do much for total confidence.

“I think it was unfortunate that when this information was first released it was released as an established fact without anyone doing any due diligence to determine how accurate it was,” Andino says. “I think that threatens the confidence that citizens have in the election process. Had I had the information before they went public with it, I think a lot of it is easily explainable, as we found out.”

Eventually, SLED and the State Election Commission will complete their tandem investigations. Hopefully they will find no instances of in-person voter fraud in the Palmetto State. In the meantime, Andino says she’ll share information about the investigation with the public as the Election Commission continues checking the names of allegedly dead voters.

In the last week or so, the state attorney general’s office hasn’t been as aggressive in perpetuating the idea of zombie voters.

In an emailed response to an interview request from Free Times to discuss the matter, Attorney General Wilson’s spokesman Plowden said he didn’t know if a meeting would be possible. And while the office neglected to engage on the issue of dead voters, it didn’t miss an opportunity to bring up another voting controversy.

“The news this office will be generating will come very shortly,” Plowden wrote, “when we file the lawsuit vs. the DOJ on the Voter ID law.”

Let us know what you think: Email editor@free-times.com.